The dust of yesterday’s mud: ten years since the Mariana disaster

Mariana still breathes mud: the disaster’s dust remains hanging between memory and identity.

by Xavier Bartira

The debris and ruins, in earthy tones, are still part of the landscape of Bento Rodrigues, a district of Mariana, in Minas Gerais, which has carried the mark of mud and neglect since 2015.

On November 5, 2015, the collapse of the tailings dam owned by the mining company Samarco, controlled by Vale and the Anglo-Australian BHP Billiton, released approximately 45 million cubic meters of toxic mud onto the district. The torrent devastated homes, lives, and rivers: 19 people died, and the Rio Doce basin was contaminated from its source in Minas Gerais to the sea in Espírito Santo.

“‘I was sitting in the watchtower and saw all the power go out’, said survivor Edson Borges. Initially he thought a water pipe had burst. ‘When I looked down, the river had already risen about four meters with mud, trees, a whole lot of stuff.’” (G1, 11/06/2015 – read here)

Many other accounts like Borges’ describe the same scenario: what was left was a wounded territory. The communities buried y the mud were promised a return – new houses, new streets, new beginnings – but the reparations came late, and for many, never fully arrived:

“We had a paradise life; everyone knew everyone […] Today there are people from Bento whom I saw being born, growing up, and haven’t seen anymore.” — José do Nascimento de Jesus, affected resident. (G1, 11/05/2025 — video here)

In Bento Rodrigues, the new settlement is only 12 kilometers from the vestiges of the old district. The streets were given the same names as before, but the architecture and the old way of life were lost. The mud dried up, but the feeling of loss has not.

In Paracatu de Baixo, another resettled community, the first house only began construction in 2021— six years after the collapse. Meanwhile, hundreds of families remain in temporary housing, awaiting a home that was promised to them amidst reports and technical assessments.

New Agreement, Old Impunity

In 2024, nearly a decade after the disaster, Samarco and its controllers, Vale and BHP, along with the government, signed a reparation agreement valued at 170 billion BRL (approx. US$32 billion with current exchange rate).

According to an official statement from Vale:

“Vale informs that Samarco, BHP and Vale, jointly with the Federal Government, the Governments of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo, Public Prosecutor’s Offices and Public Defenders’ Offices, have entered into a definitive and substantial agreement regarding the demands related to the Fundão dam collapse.” Read the full statement here.

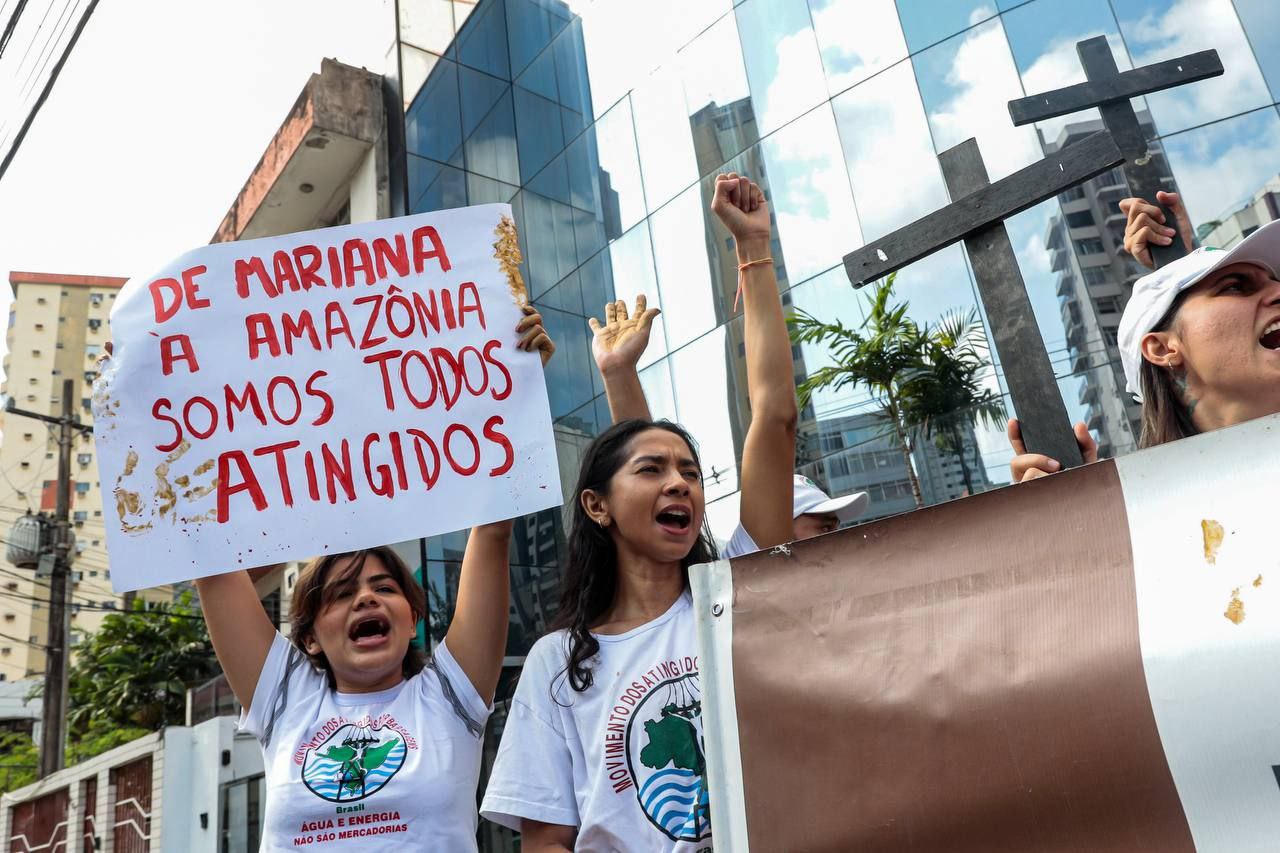

Yet, even with the new agreement, no one has been held criminally responsible. The Mariana mud remains an open wound in the country’s environmental and human history.

Brazil of the Mining Companies: Beyond the Mariana Mud

In addition to the Mariana collapse in 2015, Brazil has suffered, and continues to suffer, from other serious environmental disasters and crimes. The most similar, in scale and nature, occurred in 2019, in Brumadinho, also in Minas Gerais. Both took place in the Iron Quadrangle, a symbolic region for mining in the country. They involved the same companies — Vale, Samarco, and BHP— and resulted in catastrophic human and socio-environmental damage. Millions of cubic meters of toxic mud flowed down valleys and rivers, crossing hundreds of kilometers to the sea, leaving trails of destruction, death, and contamination.

However, dam mud is just one face of the same model of exploitation that is repeated in different forms across the country. Other large-scale environmental disasters mark our recent history: the Cesium-137 contamination in Goiânia (1987), the oil spill in Guanabara Bay (2000), and the continuous environmental crimes in the Amazon, where deforestation and fires consume entire forests, ways of life, and ancestral territories.

In Northern Brazil, the impacts of major infrastructure projects, such as large-scale hydroelectric plants and mining projects, continue to alter river ecosystems and displace traditional communities, all in the name of an economy that devastates while promising development.

The mud dried, but the dust remained, hovering, entering the lungs and thought. Mining companies do not just excavate the earth, they excavate time, flesh, and memory. What remains is a thick air, still charged with the mud of yesterday. In the country of iron and gold, life insists on being worth less than the ore.