TFFF: The Brazilian Proposal That Could Revolutionize Climate Financing

Proposal at COP30 turns forest preservation into a global economic asset, prioritizing Indigenous peoples.

by Yasmin Henrique

Brazil is preparing to present to the world, during the COP30 Leaders Summit, in Belém, the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) — one of the most ambitious initiatives ever proposed for financing environmental conservation. Conceived by the Brazilian government, in partnership with tropical nations and international investors, the TFFF proposes transforming forest preservation into an economically sustainable activity, with direct benefits for traditional peoples and for global climate stability.

Conceived at COP28, held in Dubai, in 2023, the fund will be formalized during COP30, which begins next Monday (10). The proposal breaks with the traditional donation model by adopting a self-sustaining financial structure based on long-term investments.

Unlike compensation funds, the TFFF will function as a global green investment mechanism, expected to mobilize up to US$125 billion, with US$25 billion initially contributed — including US$1 billion in Brazilian capital.

With the potential to become the largest international instrument to incentivize forest conservation, second only to the World Bank, the international initiative symbolizes a new stage in Brazilian environmental diplomacy.

As summarized by the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change (MMA), Marina Silva, “the forest needs to be seen as an economic asset, but also as a source of life and balance. The TFFF represents this new perspective.”

BRAZIL’S ROLE

The fund will operate based on a blended finance model, combining public and private resources.

The capital will be applied to projects with financial returns, and part of the earnings will be passed on to countries that keep their forests standing, according to results proven via satellite monitoring.

The amount of US$4 per preserved hectare will be distributed annually, with 20% mandatorily allocated to indigenous peoples and traditional communities.

According to Minister Marina, the TFFF represents a “game-changer” in the way resources are mobilized for nature.

“It is a robust mechanism that will allocate at least 20% to indigenous peoples and local communities. The world has always demanded preservation from tropical countries, but has never created fair compensation mechanisms,” she maintained.

The Minister of Indigenous Peoples, Sonia Guajajara, highlighted the historic nature of the initiative. “Only 1% of climate resources reach indigenous territories. The TFFF corrects this injustice. It is not just about money, but, essentially, about respect, autonomy, and recognition of the forest peoples,” she said.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva reinforced the fund’s strategic role: “Brazil is once again leading the climate debate with concrete proposals. The TFFF is proof that it is possible to grow and preserve at the same time.”

Lula discussed the proposal at the 80th United Nations General Assembly, held between September 9 and 27 in New York.

The monitoring and transparency system is considered one of the pillars of the project. The measurement of conserved areas will be done by satellite images with international standardization and public access to the data, with the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe) as a technical reference.

This structure is reinforced by the National Environmental Council (Conama) resolution No. 510/2025, which establishes national standards for authorizations of vegetation suppression and public deforestation audits.

INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT

The fund has the support of countries such as Germany, France, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates. Financial institutions, such as one of the world’s largest investment managers, the Pacific Investment Management Company (PIMCO) and two of the main global financial institutions, the US-based Bank of America and the British Barclays, are also part of the initiative.

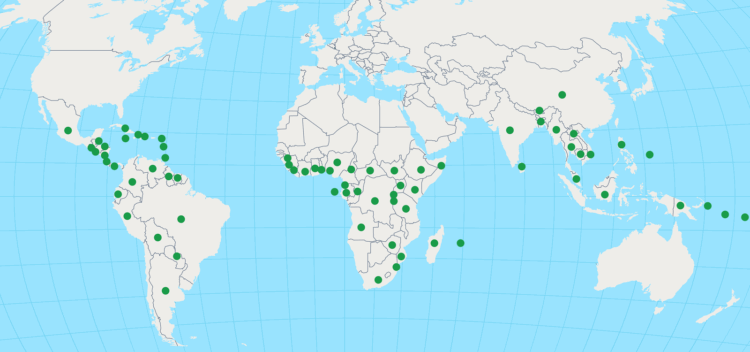

Organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC), which represents 35 million people in 24 countries, are also among the corporations that support the financial reserve.

The General Coordinator of the GATC, Tuntiak Katan, emphasizes that “when forest peoples have direct access to financing, the result is real protection, not just a promise.”

The mechanism is also distinguished by its territorial and inclusive approach, ensuring the direct sharing of benefits with local communities.

For the UK Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, Ed Miliband, it is “a bold proposal that unites the Global North and South in favor of forests.”

The Norwegian Minister of Climate and Environment, Andreas Eriksen, emphasized that the TFFF “can transform forest financing, provided it maintains strong environmental and social safeguards.”

In the view of the UNDP Administrator, Achim Steiner, the fund “creates long-term incentives to keep forests standing, uniting financial credibility and environmental justice.”

The UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance (UNCAF), Mark Carney, classified the TFFF as “a new paradigm, capable of redefining what it means to invest in nature.”

Project Challenges

Despite the enthusiasm, the project faces challenges. Experts from the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) warn of the risk of undercapitalization – an excessive level of indebtedness – and the international context of contraction in climate cooperation.

Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) indicate that global military spending reached US$2.7 trillion in 2024.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) forecasts a drop of up to 17% in assistance for sustainable development by 2026.

Critics from social movements, such as the Landless Workers Movement (MST), point out that the proposed value per hectare is symbolic compared to the profit generated by agricultural and livestock activities.

The MST adds that the fund may reinforce the logic of “financialization of nature,” the monetization of ecosystem services — such as carbon sequestration, water maintenance, and climate regulation.

Furthermore, the resources would be managed by the Ministries of Finance, without direct transfer to local communities — which could receive, at most, 20% of the total.

The model, which is dependent on private investments, makes conservation subject to market volatility and could generate new ecological debts for the Global South countries.

Although it does not directly create carbon credits, the TFFF integrates into the environmental compensation logic of mechanisms such as the Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), reinforcing the idea that it is possible to continue polluting upon payment.

In contrast, socio-environmental movements advocate for a model based on territorial sovereignty, social control, and democratic management of forests, rejecting the financialization of nature and restoring prominence to the communities that protect them.

https://tfff.earth/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Concept-Note-3.0-PT.pdf