KUMARUARA, A PEOPLE WITH THE NAME OF THE CURE

O povo indígena da Aldeia Solimões contou com o fruto nativo que deu nome à etnia para auxiliar no processo de cura durante os picos da Covid-19

O Pajé Nato Tupinambá benzendo uma indígena

Cumaru is the fruit that grows from the flower of the tropical tree Cumarueira, typical throughout the northern region of South America—including the Brazilian states of Amazonas and Pará. Outside the Amazon, it is recognized as one of the most exquisite and exotic spices in gourmet cuisine, replacing others such as cinnamon or clove. In some countries, Cumaru is seen as a poison: the US, for instance, has banned its consumption since 1954, according to the BBC. But, inside the Amazon, it is a sacred plant, used to treat respiratory diseases, among other ailments.

Kumaruara comes from Cumaru, and is the name of one of the 13 Indigenous peoples that inhabit the Lower Tapajós region, in the west of Pará state. The Solimões Indigenous village, located on the right bank of the Tapajós River, is inhabited by this people, who recognize Cumaru as a plant that bears the essence of identity and healing. Now, during the pandemic, it was widely used to help treat Covid-19, contributing to the cure of many Kumaruara infected by the virus.

Chief Leno, next to a cumaru tree

““Our ancients, our ancestors, spoke and speak even now that, here inside our territory, there was a lot of this tree called Cumaru, so our ancients named our ethnic group Kumaruara. We fought a lot of Covid with Cumaru, all the villages widely used this medicine. It seems that our ancestors knew how to name the cure,” explained Leno Kumaruara, chief of the Solimões Village.

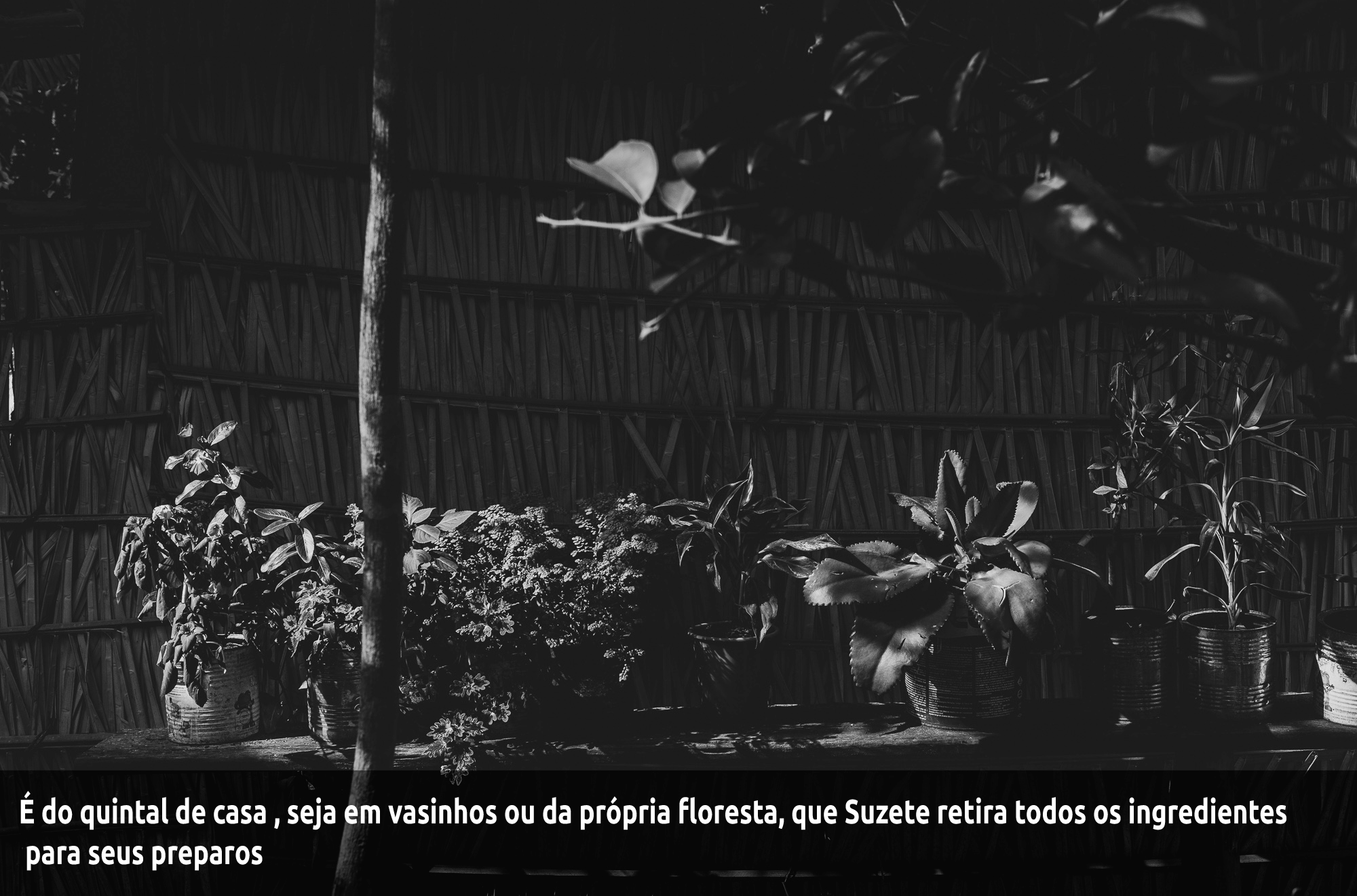

It is from her backyard that the experienced shaman Suzete obtains the leaves, bark, fruits and seeds that are used to make the medicines that help her people

The Solimões village, a two-hour trip from Santarém, the second largest city in Pará, has been in the process, since the past decade, of recognition of this traditionally occupied territory. The National Indian Foundation (Funai) has not yet demarcated this area of traditional Indigenous occupation that overlaps the interior of the Tapajós-Arapiuns Extractive Reserve. This overlapping causes conflicts, as well as omission and lack of assistance to Indigenous peoples. The descendants of the Cabanagem warriors today suffer from the lack of basic services, such as health care and education, and from the invisibility of their ethnic condition.

According to the report “O Brasil com baixa imunidade – Balanço do Orçamento Geral da União 2019” [Brazil with low immunity – Balance of the 2019 Federal General Budget], published by INESC, an institute specializing in public budget and human rights in Brazil, the Indigenous sanitation policy was an important chapter in the attack on the rights not only of the Kumaruara people, but of all Indigenous peoples in Brazil.

The “Uca do Remédio” (healing house) is where Shaman Suzete “pulls”,

blesses and distributes her “bottles” (traditional medications that serve for all kinds of health problems)

“In 2019, the execution of the budget was R$ 1.48 billion against R$ 1.76 billion in 2018, about R$ 280 million less. This certainly compromises assistance for this group of the population, with many health indicators generally worse than the Brazilian average, such as suicide, malnutrition and infant mortality, and some infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis,” informs the report.

In health, traditional knowledge was the most used in the most critical periods of the pandemic, and the presence of shamans working on the front lines helped more people to recover from the virus. They were a vital pillar to ensure that many Indigenous people could have access to assistance in the face of the current administration’s denialist, criminal agenda.

Shaman Suzete evokes the spirits while preparing one of her many medications

With the Cumaru in hand, Suzete Kumaruara, a shaman from the Solimões Village, says she helped many of her relatives to get out of the hammock—affected by Covid-19—and recover their breathing. She, who is 75, was at the front lines of health assistance in her village during the worst moments of the pandemic. Santarém, the closest city, has already “raised the black flag” at two different times, which means maximum alert for those infected with Covid-19, and also a high number of hospitalized patients, a demand greater than what the health clinics in the region were able to handle.

“Cumaru is very important because from it you make perfume, medication, you mix its pulp to make an ointment, from its oil you make a solution for sore throat, when you feel it burn. We can’t do without Cumaru here. We used to get the milk (from the Cumaru) for Covid, because it was good for that, it was a very good medication for this disease,” explains the shaman about the main resource for going through crucial moments.

.

As a spiritual leader, Suzete explains that the shaman’s presence is a form of healing safeness for the village, and also the bond that links the spirit to nature. According to her experience, this is how healing happens: in believing that “healing comes from above and from the enchanted ones.”

“Where does the medication come from? From nature, you see, it’s where we will look for where it is, for us to prepare the baths, so that people can get better. The healing power comes from God, and other things come from the enchanted ones, because the enchanted ones, they also make many medications and teach too, and they make their healing, the deep cure is this.”

.

The power of the enchanted ones has always accompanied Shaman Suzete

The shaman’s knowledge came from the cradle. She says that, in addition to the gift of making medicines, she is also a “puller,” a blesser and a midwife. She acquired all her knowledge through dreams or the presence of the enchanted ones, when connecting with nature. Today, Suzete produces medication for her community, and also supplies them to other villages when necessary.

“My cure comes from above; at the beginning I had doubts about doing something and it failing to work. Then I understood that I wasn’t supposed to have these doubts, or even fear. I could work with no concerns, because, if I was in doubt, then with fear nothing would work. That’s what I heard, so I put it all aside and kept going.”

Through her touch, Suzete investigates body ailments

Now, already vaccinated, the shaman from the small village of less than 50 people feels safer to continue helping her community, and appeal for her relatives to adhere to the vaccination. “I tell everyone who listens to me to get the vaccine and take care of themselves, use hand sanitizer, wear a mask and don’t get too close to each other, because it’s not over yet, and we need to have love in our family, in our life, because that’s what is most important for us,” she concludes.

The Solimões Village is located on the right bank of Lower Tapajós

Access to healthcare in the Lower Tapajós

Since 2015, the indigenous peoples of the Lower Tapajós, through the Tapajós and Arapiuns Indigenous Council (Cita), have been claiming access to Indigenous health care. In 2016, the Sesai’s Polo Base in Santarém was occupied. After the occupation, the villages gained access to the right to health care through a court decision based on a public civil action by the Federal Public Prosecutor (MPF).

The Solimões Village and other communities and villages in the Resex Tapajós-Arapiuns suffer from a lack of basic health care

Even with the recognition, the main struggle of the Indigenous peoples in the municipalities of Aveiro, Santarém and Belterra remains the same as it was five years ago: the creation of a new Special Indigenous Sanitary District (DSEI) for the region. Currently, Santarém is included in the DSEI Guamá-Tocantins, headquartered in Belém, 1,375.8 kilometers from the village, that is, approximately 22 hours by land transport, which makes access to health care even more problematic.

“The government’s legislative and executive measures demonstrate that an agenda for the intentional and systematic destruction of the ways of living and culture of Indigenous peoples is underway,” the INESC report points out.

The intrinsic relationship of the Kumaruara people with the cumaru tree

Galeria

Reportagem especial: Mídia Ninja e Amazon Watch

Reportagem: Tainá Aragão

Fotos: Leonardo Milano

Vídeos: Priscilla Tapajoara

Edição de Vídeo: Benjamin Mast

Design: Yasmim Moura, Aruan Mattos

Diagramação e montagem: Kelly Mariah Batista