From Rio 92 to Belém 25: Brazil’s Role in Climate Negotiations

From the conference that launched climate diplomacy to COP30 in the Amazon, Brazil strives to turn leadership into results.

by Yasmin Henrique

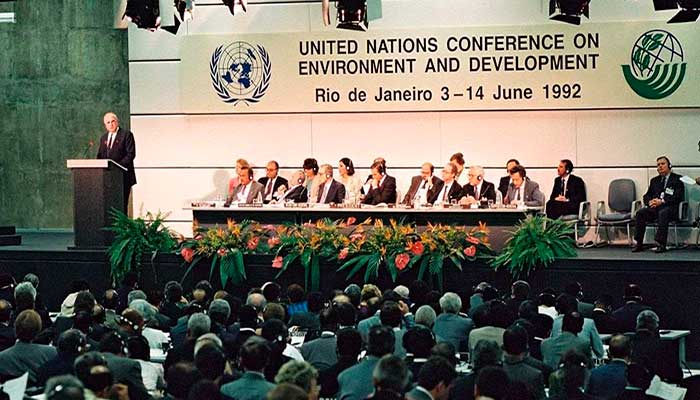

Thirty-three years separate the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development — the historic Rio 92 — from the next COP30. In this period, Brazil transitioned between protagonism — as host of the meeting that inaugurated modern climate governance, influencing agreements that shaped global climate policy — and isolation — when from 2019 to 2022 it allowed enforcement actions against deforestation to weaken and was internationally criticized.

Rio 92 gathered over 170 heads of state and about 30,000 participants, according to the United Nations (UN). Three of the main current environmental treaties were born from it:

- the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

- the Convention on Biological Diversity (CDB)

- the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

It was also at Rio 92 that the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” actively advocated by Brazilian diplomacy, was formalized. The logic is simple: everyone must act against global warming, but developed countries — responsible for the majority of historical emissions, according to the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) — need to do more. From then on, annual meetings began to be held, the Conferences of the Parties (COPs).

Kyoto Protocol, PPCDAm, and the Paris Agreement

Five years after Rio 92, in 1997, countries negotiated the Kyoto Protocol. Brazil had no legal obligation to reduce emissions because it was a developing country, but it played a determining role in the creation of one of the agreement’s main instruments: the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The mechanism was inspired by a technical proposal presented by the Brazilian delegation, recorded in the negotiation annals of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

With the CDM, industrialized countries could offset part of their emissions by investing in renewable energy and conservation projects in developing countries. In the following decade (2000 to 2010), Brazil became one of the leaders in registering CDM projects, according to the World Bank.

In 2004, the country launched the PPCDAm — Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon, involving enforcement, land regularization, and satellite monitoring. The result was historic: deforestation in the Amazon fell by 83% between 2004 and 2012, according to the document from the 5th phase (2023-2027) of the PPCDAm.

This reduction made Brazil, for some years, one of the countries that most contributed to reducing global emissions. Data from the SEEG (System for the Estimation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals) show that, during this period, the drop in deforestation was the main factor for the reduction of Brazilian emissions.

TIMELINE OF COPs UNTIL LIMA (2014): https://widgets.socioambiental.org/widgets/timeline/535#0

At COP21, in Paris (2015), countries signed the Paris Agreement, establishing the limit for the increase in global warming at 1.5°C. Brazil presented its first NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution), promising to:

- reduce 43% of emissions by 2030 (2005 baseline);

- restore 12 million hectares of forests;

- expand the use of renewable energy.

The goals were officially registered with the UNFCCC. At that time, the country was praised for combining ambition and implementation capacity — supported by an already majority-renewable electricity matrix.

Isolation and backsliding (2019–2022): the height of international distrust

Between 2019 and 2022, changes in Brazilian environmental policy generated international criticism, such as that from the Greenpeace spokesperson in Brazil in 2020. Enforcement was weakened, and scientific data was even publicly contested. According to the consolidated deforestation rate for the nine states of the Brazilian Legal Amazon (ALB) — developed by the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) —, deforestation in the Amazon grew by 59% during the period, reaching the highest level in 15 years.

Reports from Global Forest Watch also indicate that Brazil led the loss of tropical forests globally during this period. The reputation as a climate mediator was replaced by questioning from other countries in the COPs plenary.

Starting in 2023, with the resumption of environmental policies, deforestation started to fall again. INPE data shows a 22.4% reduction in the Amazon between August 2022 and July 2023. At COP28, in Dubai, the UNFCCC announced Belém do Pará as the host city for COP30, in 2025.

Belém 25: the COP of delivery

It will be the first COP in the heart of the Amazon. For specialists, the gesture is symbolic: the climate debate returns to the central point — the forest. The Conference marks the deadline for all countries to present new, more ambitious climate targets compared to those proposed in the Paris Agreement. In preparation for this edition, webinars held by the Government, strategies implemented in 2024, and demands from the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB); Brazil will advocate for:

- new climate finance mechanisms;

- valuation of indigenous peoples as protectors of the forest;

- bioeconomy as a regional development strategy.

From the host of the meeting that inaugurated modern climate governance — at Rio 92 —, the country now arrives as a candidate for leader of the ecological transition at COP30. Documents from Itamaraty indicate that the country wants to lead the financing agenda for Global South countries, demanding that wealthy nations fulfill the promise to contribute US$100 billion annually for climate action, a promise made at COP15 (Copenhagen, 2009) and only partially fulfilled, as shown in a 2023 report by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Rio 92 opened the path; Belém could be the turning point.